It is common knowledge that that modern day US CEOs are trashy, lying, cheating scum of the earth, and in general despicable, execrably abhorrent slimy and oily characters.

But not all of them! Some have hearts of gold. I want to highlight one such person on Christmas Day.

Greed is not good. And on Christmas Day, I want to say unChristian as well. I wish each one of us get a boss like Mr Graham Walker. Thank you Sir for being the awesome person you are. I pray to God to bless the man for helping so many people.

Link is below. Read the entire article. It is heart-warming.

The boss who gave his employees a $240 million gift

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/companies/the-boss-who-gave-his-employees-a-240-million-gift/ar-AA1SZwmn

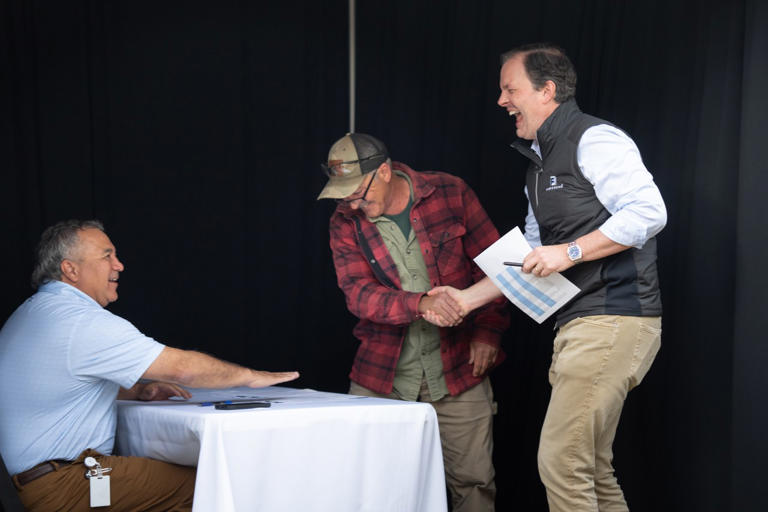

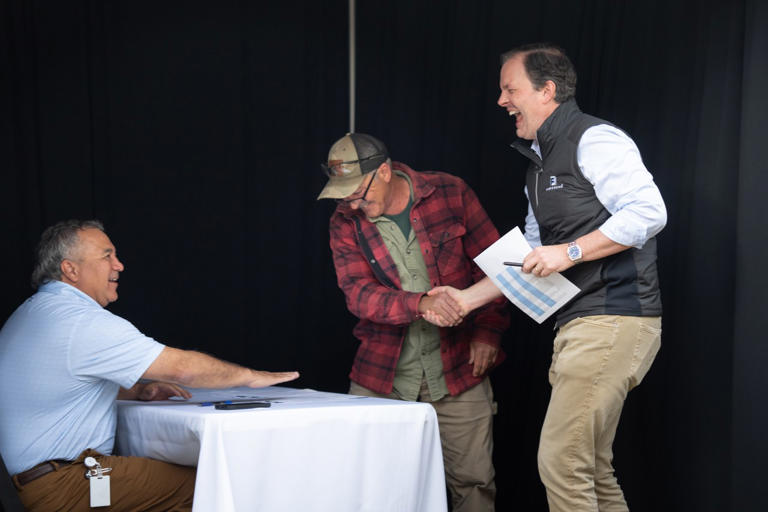

A Fibrebond employees shakes Walker's hand as he learns the size of his bonus.

But not all of them! Some have hearts of gold. I want to highlight one such person on Christmas Day.

Greed is not good. And on Christmas Day, I want to say unChristian as well. I wish each one of us get a boss like Mr Graham Walker. Thank you Sir for being the awesome person you are. I pray to God to bless the man for helping so many people.

Link is below. Read the entire article. It is heart-warming.

The boss who gave his employees a $240 million gift

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/companies/the-boss-who-gave-his-employees-a-240-million-gift/ar-AA1SZwmn

Quote:

In March, Lesia Key was summoned to meet her boss, Graham Walker, near the factory where they worked.

At an outside table, Walker thanked Key for her 29 years of service. Then, a colleague handed her a sealed, blue-and-white envelope. She opened it and broke down crying, as Walker struggled to compose himself.

Walker was giving Key, 51, a life-altering sum of moneyand he was doing the same for his 539 other full-time employees.

Walker and his family started a company in Minden, La., called Fibrebond, which makes enclosures for electrical equipment. Earlier this year, he agreed to sell the business to Eaton, a power-management company, for $1.7 billion.

Walker wanted to reward employees, grateful that so many had stuck with his company through tough times, before it found new life building enclosures for data centers. So he included a condition into the terms of the transaction: 15% of the sale proceeds would go to his employees.

In June, his 540 full-time employees began receiving $240 million in bonuses. The average bonus was $443,000, to be paid over five years, as long as the employees remained at the company for that period. Long-timers received much more.

On the day the money was distributed, staffers stared at their bonus letters in disbelief. A few thought they were being pranked. Many were emotional. Since then, they've used the cash to slash debt, buy cars, pay college tuition and fund retirements. One took his entire extended family to Cancn. The cash has lifted spirits and boosted business in Minden, a city of roughly 12,000 people located about 30 minutes east of Shreveport, La.

"Some spent it on day one, maybe even night number one," says Walker, 46. "Ultimately, it's their decision, good or bad."

Lesia Key started at Firebond in 1995, making $5.35 an hour. She was a 21-year-old with three young children and a pile of debt. She began in the finishing department, cleaning and packing items before they were shipped to customers. On the side, she cleaned houses for extra cash, but that wasn't enough to avoid bankruptcy. Over the years, she rose through the ranks as her personal life steadied. By early this year, she led a team of 18 people managing the company's facilities on 254 acres.

She used her bonus to pay off her home mortgage and fulfilled a lifelong dreamopening a clothing boutique in a nearby town.

"Before, we were going paycheck to paycheck," she says. "I can live now; I'm grateful."

Lesia Key used some of her bonus to open a clothing store. SheRon Casey

It's not unusual for staffers to share the wealth when a company is sold or enjoys a lucrative initial public offering. Silicon Valley is full of stories of secretaries and others benefiting from big IPOs. But those employees generally own shares of their companies. It's much rarer for those who don't own a piece of a business to benefit from a big sale. That's what makes the Fibrebond story so distinctive.

The company's success is just as unlikely. In 1982, Walker's father, Claud Walker, used proceeds from the sale of a different business to start Fibrebond. The 12-man company built structures for telephones and electrical equipment alongside train tracks. In the 1990s, it pivoted to concrete enclosures for cellphone towers, thriving as that industry expanded.

But Fibrebond's factory burned to the ground in 1998, decimating its business. It took months to restart operations. Claud and the family continued paying salaries, employees say, building loyalty. The company enjoyed a surge of demand in 2000, but it dissipated when the dot-com bubble burst. By the early 2000s, Fibrebond was down to just three customers, forcing the company to slash its number of employees to 320 from about 900.

In the mid-2000s, Graham Walker and his brother began running Fibrebond, after doing menial jobs and later taking on more senior roles at the company. Once they were in charge, they spent two years selling assets and paying down debt. They tried unsuccessfully to enter new markets, including constructing classrooms for schools.

A Fibrebond employees shakes Walker's hand as he learns the size of his bonus.