As 1863 closed on December 9, Robert E. Lee was on a special train from his headquarters at Orange CH in central Virginia bound for Richmond. Lee was to meet the next day with President Jefferson Davis, to discuss who should command the Army of Tennessee. The former commander, Braxton Bragg, had been relieved from duty two weeks before. Davis had already hinted to Lee that he wanted him to take the command and Lee feared that the meeting tomorrow would result in Davis ordering him to command the Army of Tennessee. Before boarding the train, Lee dispatched orders to his cavalry commander JEB Stuart to find positions for his cavalry, where they had forage for the horses, he also off-handedly addressed rumors Stuart and the rest of the army had been hearing. Lee added an uncharacteristic passage in this message, "I am called to Richmond this morning by the President. I presume the rest will follow. My heart and thoughts will always be with this army."

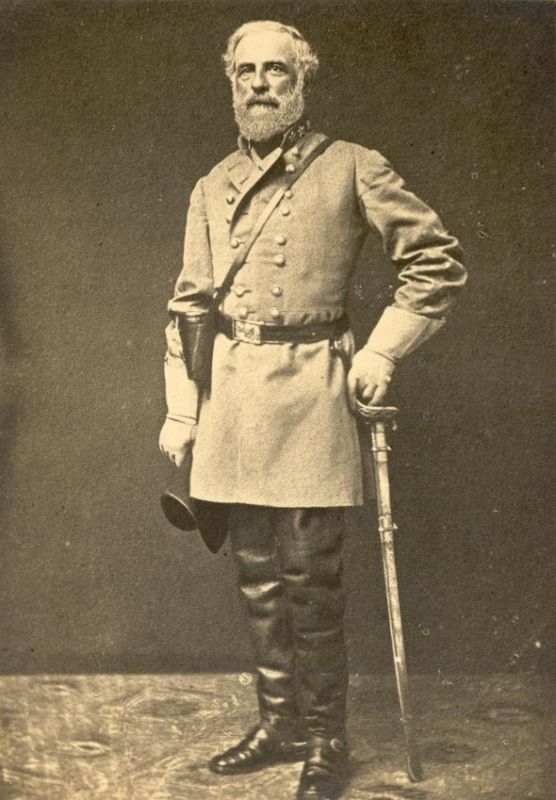

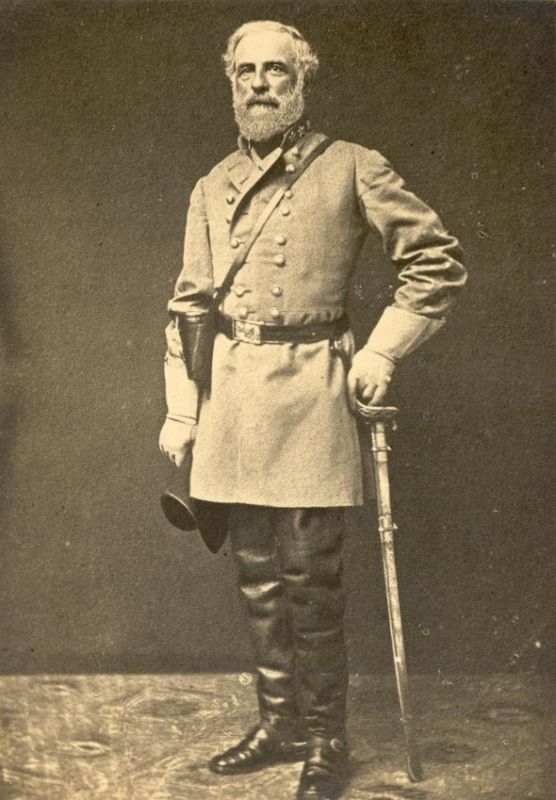

Robert E. Lee as he appeared the month after his trip to Richmond.

1863 had been a very bad year for Lee both personally and professionally. In April, he had "a very bad cold," which was probably angina and the first appearances of circulatory health issues that would kill him in seven and a half years. In May, he had won what many call his greatest victory at Chancellorsville. But on the first day, his most like-minded lieutenant, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson had been mortally wounded by his own men and the second day was the bloodiest morning of the war, with many of Lee's men wasted on attacking Federals in entrenched positions. In June, he had embarked on an ambitious and physically taxing invasion of Pennsylvania to destroy the anthracite coal district north of Harrisburg. In July, he fought the bloodiest battle of the war at Gettysburg, which ended Lee's invasion of the north. During the battle Lee had suffered terribly from diarrhea and a recurrence of a bout with malaria, from his days building Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor. In August, he tendered his resignation from the army, citing his health issues, but Davis had refused it. Two disappointing campaigns occurred in the fall. In October Lee had sought to destroy a portion of the Army of the Potomac under George G. Meade at Bristoe Station but an impetuous charge by A.P. Hill had left nearly 1,400 unnecessary casualties. The morning after the battle, Lee visited the battlefield with Hill. Hill manfully and sorrowfully took the blame for the loss. Lee obviously glum and disappointed cut Hill's description of the battle off with words that must have cut Hill to his soul, "Well, well General, bury these poor men and let us say no more about it." In November, Lee had laid a trap for the Army of the Potomac at Mine Run but Meade was clever enough to see it and not take the bait. Rheumatism had bothered Lee through the fall and into the winter so that at times, he was confined to bed and he could not mount a horse. Meanwhile, his wife's arthritis had reached a point where she was confined to wheelchair and her health was also in peril.

Alfred Waud sketch of the misbegotten attack by Hill at Bristoe Station

For the long, creaky commute to Richmond on the Virginia Central Railroad, Lee took along personal correspondence and like a modern commuter, used the time to catch up. One letter he read on the trip was from two teenaged girls from Richmond, Lucy Minnegerode and Lou Haxall. Lee was acquainted with the girls and their families from social functions he had attended in Richmond. Lucy was the daughter of the rector of St. Paul's Episcopal, where all the big Confederate officials went to Sunday services. Lou was the daughter of a wealthy flour miller. The girls wrote to Lee:

Lucy Minnegerode

Upon arrival at the station in Richmond, Lee made his way up town to the humble wooded two-story house he rented on Leigh Street between Second and Third to visit with his wife, oldest son Custis and his daughters, before making his way to the Confederate White House the next day. In the meeting with Davis, before the president could ask him to take the command of the Army of Tennessee, Lee proposed P.G.T. Beauregard, even though he knew that Davis loathed him. Naturally, Davis rejected this proposal and Lee then suggested Joseph E. Johnston. Davis had almost as many issues with Johnston as he did with Beauregard but Lee convinced Davis it was the correct choice.

Photograph of Lee and Johnston taken six months before Lee's death

After returning home from the White House, Lee sent a note to William Mahone, Robinson's brigade commander, saying that if the needs of the service permitted, he should give Robinson a ten-day furlough to include Christmas Day. Lee was familiar with Robinson and knew that his younger brother, Willie, was one of the soldiers that A.P. Hill had to bury at Bristoe Station. After writing Mahone, Lee then wrote a note to Robinson, telling him of his request and to express his sympathy at the loss of his brother. Then Lee decided to have some fun with his "two little friends" and wrote them a note:

Cary Robinson in Confederate Uniform

Willie Robinson

Lee, had not spent a Christmas with his family since 1859 and 1863 would be no different than the previous three years. Lee boarded a train on the 21st and returned to the army at Orange CH. There is no record of how Christmas 1863 went for Cary Robinson but one may only wish that it was a pleasant one. Cary had been born in Richmond on November 9, 1843 the son of a legal scholar and author of a well-known law book, Conway Robinson. Cary attended primary education at Mr. Turner's School in Richmond. In 1858, the family moved to Washington D.C and Cary enrolled in Columbia College (now George Washington University). When the war came, Cary and his younger brother Willie, who was 16 at the time, had to cross Federal lines in October 1861 to enlist in Company G of the 6th Virginia Infantry. Cary was apparently as popular with his comrades in arms as he was with the ladies. He was selected to be the Sergeant Major of the regiment on August 24, 1864. As the Overland Campaign progressed and the Texas Brigade's numbers dwindled, Mahone's Brigade became Lee's shock troops during the fighting around Petersburg. On October 27, 1864, Cary was killed in an attack by Mahone's Brigade on the Boydton Plank Road, two weeks short of his 21st birthday. His obituary in the Richmond Examiner read:

Here is a photograph of Cary from the family album about the time he was at Columbia. I find it more poignant than the one of him in uniform, especially with the notation made by one family member, "Killed in our War." Why did they write "our" instead of "the?" Were they defiant, proud or remorseful, I would love to know?

Robert E. Lee as he appeared the month after his trip to Richmond.

1863 had been a very bad year for Lee both personally and professionally. In April, he had "a very bad cold," which was probably angina and the first appearances of circulatory health issues that would kill him in seven and a half years. In May, he had won what many call his greatest victory at Chancellorsville. But on the first day, his most like-minded lieutenant, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson had been mortally wounded by his own men and the second day was the bloodiest morning of the war, with many of Lee's men wasted on attacking Federals in entrenched positions. In June, he had embarked on an ambitious and physically taxing invasion of Pennsylvania to destroy the anthracite coal district north of Harrisburg. In July, he fought the bloodiest battle of the war at Gettysburg, which ended Lee's invasion of the north. During the battle Lee had suffered terribly from diarrhea and a recurrence of a bout with malaria, from his days building Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor. In August, he tendered his resignation from the army, citing his health issues, but Davis had refused it. Two disappointing campaigns occurred in the fall. In October Lee had sought to destroy a portion of the Army of the Potomac under George G. Meade at Bristoe Station but an impetuous charge by A.P. Hill had left nearly 1,400 unnecessary casualties. The morning after the battle, Lee visited the battlefield with Hill. Hill manfully and sorrowfully took the blame for the loss. Lee obviously glum and disappointed cut Hill's description of the battle off with words that must have cut Hill to his soul, "Well, well General, bury these poor men and let us say no more about it." In November, Lee had laid a trap for the Army of the Potomac at Mine Run but Meade was clever enough to see it and not take the bait. Rheumatism had bothered Lee through the fall and into the winter so that at times, he was confined to bed and he could not mount a horse. Meanwhile, his wife's arthritis had reached a point where she was confined to wheelchair and her health was also in peril.

Alfred Waud sketch of the misbegotten attack by Hill at Bristoe Station

For the long, creaky commute to Richmond on the Virginia Central Railroad, Lee took along personal correspondence and like a modern commuter, used the time to catch up. One letter he read on the trip was from two teenaged girls from Richmond, Lucy Minnegerode and Lou Haxall. Lee was acquainted with the girls and their families from social functions he had attended in Richmond. Lucy was the daughter of the rector of St. Paul's Episcopal, where all the big Confederate officials went to Sunday services. Lou was the daughter of a wealthy flour miller. The girls wrote to Lee:

Quote:

We the undersigned write this little note to you our beloved Gen. to ask a little favor of you which if it is in your power to grant we trust you will. We want Private Cary Robinson of Com. G, 6th V, Mahone's Brig. To spend Christmas with us, and if you will grant him a furlough for this purpose we will pay you back in thanks and love and kisses. Your two little friends, Lucy and Lou.

Lucy Minnegerode

Upon arrival at the station in Richmond, Lee made his way up town to the humble wooded two-story house he rented on Leigh Street between Second and Third to visit with his wife, oldest son Custis and his daughters, before making his way to the Confederate White House the next day. In the meeting with Davis, before the president could ask him to take the command of the Army of Tennessee, Lee proposed P.G.T. Beauregard, even though he knew that Davis loathed him. Naturally, Davis rejected this proposal and Lee then suggested Joseph E. Johnston. Davis had almost as many issues with Johnston as he did with Beauregard but Lee convinced Davis it was the correct choice.

Photograph of Lee and Johnston taken six months before Lee's death

After returning home from the White House, Lee sent a note to William Mahone, Robinson's brigade commander, saying that if the needs of the service permitted, he should give Robinson a ten-day furlough to include Christmas Day. Lee was familiar with Robinson and knew that his younger brother, Willie, was one of the soldiers that A.P. Hill had to bury at Bristoe Station. After writing Mahone, Lee then wrote a note to Robinson, telling him of his request and to express his sympathy at the loss of his brother. Then Lee decided to have some fun with his "two little friends" and wrote them a note:

Quote:

I rec'd the morning I left camp your joint request for permission to Mr. Cary Robinson to visit you on Xmas, and gave authority for his doing so, provided circumstances permitted. Deeply sympathizing with him in his recent affliction it gave me great pleasure to extend to him the opportunity of seeing you, but I fear I was influenced by the bribe held out to me, and I will punish myself by not going to claim the thanks and love and kisses promised me. You know the self denial this will cost me. I fear too I shall be obliged to submit your letter to Congress, that our Legislators may know the temptations to which poor soldiers are exposed, and in their wisdom devise some means of counteracting its influence. They may know that bribery and corruption is stalking boldly over the land, but may not be aware that the fairest and sweetest are engaged in its practice.

Cary Robinson in Confederate Uniform

Willie Robinson

Lee, had not spent a Christmas with his family since 1859 and 1863 would be no different than the previous three years. Lee boarded a train on the 21st and returned to the army at Orange CH. There is no record of how Christmas 1863 went for Cary Robinson but one may only wish that it was a pleasant one. Cary had been born in Richmond on November 9, 1843 the son of a legal scholar and author of a well-known law book, Conway Robinson. Cary attended primary education at Mr. Turner's School in Richmond. In 1858, the family moved to Washington D.C and Cary enrolled in Columbia College (now George Washington University). When the war came, Cary and his younger brother Willie, who was 16 at the time, had to cross Federal lines in October 1861 to enlist in Company G of the 6th Virginia Infantry. Cary was apparently as popular with his comrades in arms as he was with the ladies. He was selected to be the Sergeant Major of the regiment on August 24, 1864. As the Overland Campaign progressed and the Texas Brigade's numbers dwindled, Mahone's Brigade became Lee's shock troops during the fighting around Petersburg. On October 27, 1864, Cary was killed in an attack by Mahone's Brigade on the Boydton Plank Road, two weeks short of his 21st birthday. His obituary in the Richmond Examiner read:

Cary lies in the family plot in Section E of Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, surrounded by hundreds of other Confederate heroes.Quote:

[H]e always desired to die at the head of the old brigade…splendid in his dauntless bravery, genial in his temper, full of innocent mirth, rarely gifted in mind… softened & enabled by a sweet spirit of Christian love & faith… the cause has lost a courageous defender, society a refined and accomplished gentleman, and the service of Christ, on earth, a faithful and loving disciple… [H]e once said…his noble boyish face illuminated by the beauty of holiness, "If God sees fit to take me I am perfectly contented"…[H]e has received his promotion into the noblest army of martyrs.

Here is a photograph of Cary from the family album about the time he was at Columbia. I find it more poignant than the one of him in uniform, especially with the notation made by one family member, "Killed in our War." Why did they write "our" instead of "the?" Were they defiant, proud or remorseful, I would love to know?