Photo by Taking Flak

Lopez: Excerpt of my new book with Dan Pastorini

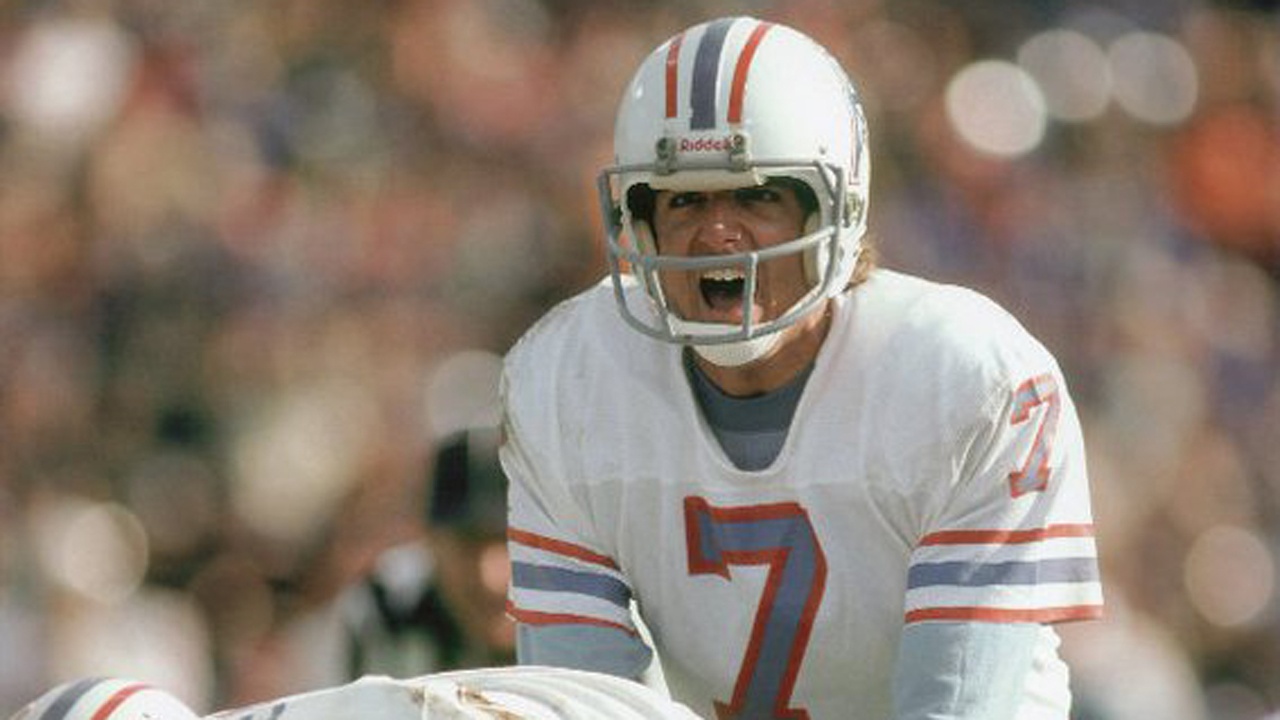

He was an NFL superstar and Drag Racing icon. He had Hollywood starlets on his arm and a legion of fans in the palms of his hands. Dan Pastorini lived on the edge and played on the brink. No one — least of all Pastorini — knew what the next turn would bring. His life was indulgent, brilliant, cursed and humbling. He was known as the toughest man in football, a cover-boy heart-throb and a soft-hearted friend. He changed the way NFL quarterbacks played the game, donning the first Flak Jacket to protect three shattered ribs. He threw perhaps the most fateful pass in playoff history, a controversial championship moment that led to use of NFL replay.

He was involved in a tragic speed boating accident. He beat “Big Daddy” Don Garlits and all of drag racing’s best. He was the hero in the most triumphant return an NFL team ever received. He never backed down from anything or anyone, falling into notorious scrapes and life-altering lows. He married a Playboy model and posed for Playgirl. He dated Farrah Fawcett and was the most iconic figure in a Wild West era when Texas oil boomed and gluttony prevailed. Dan Pastorini never has told the whole story. Until now. This is the story of a gifted, hard-driving kid from California who never stopped going fast or chasing dreams.

No matter how much flak he took.

The following is an excerpt of the new book entitled "Taking Flak: My Life in the Fast Lane." It's co-authored by Pastorini and me and we would love if you guys would check out the excerpt and see if this book is something that would be of interest to you.

A few weeks before training camp in 1977, Don Meredith put together a quarterback legends charity golf tournament in Hawaii. It was a great event and a good time for me to get away. Some of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history were invited, as well as quarterbacks of my era like Roger Staubach and Tommy Kramer. Bobby Layne was there. Billy Kilmer. Johnny Unitas. Sonny Jurgenson. It was a posh event, sponsored by a hotel chain and supported by huge corporate sponsors. Bobby Layne was social chairman, so it basically was three days of golf, booze and stories.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"left","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12023}

Tommy Kramer and I were playing catch on the grass in front of the hotel before cocktail hour one evening, when Billy Kilmer started hollering at me from the balcony of his fourth-floor room. Apparently he was bragging about my arm strength to Bobby Layne, Johnny Unitas and sportswriter Dan Jenkins, all of whom were sitting on the balcony with Kilmer having cocktails, solving the world’s problems and talking about quarterbacks.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"left","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12023}

Tommy Kramer and I were playing catch on the grass in front of the hotel before cocktail hour one evening, when Billy Kilmer started hollering at me from the balcony of his fourth-floor room. Apparently he was bragging about my arm strength to Bobby Layne, Johnny Unitas and sportswriter Dan Jenkins, all of whom were sitting on the balcony with Kilmer having cocktails, solving the world’s problems and talking about quarterbacks.

“Throw the ball up here,” Kilmer shouted. “Hit me, Dante. Can you hit me?”

Naturally, I wasn’t going to let a chance to show off pass me by. I cocked my arm and threw a perfect spiral as hard as I could. The ball sailed perfectly over their heads, above the balcony, above the next floor and hit a 10th-story balcony.

Jenkins turned to Bobby Layne and said, “Did you see that? Can you believe the arm strength in that kid? Can you believe he threw a football up 10-stories?”

Unitas chimed in, “Yeah, but his receiver was on the fifth floor.”

I laughed when I heard what Unitas said, but those were the kinds of comments that grated on me. That’s how my career was defined. He’s got a great arm, but …

Another quarterback legend, John Hadl, helped me a lot in 1977. He was a 14-year veteran that had seen it all. He convinced me to just keep working like I was working and keep playing hard. Hadl and I got along great, too, because he really knew football and liked having a good time off the field.

About three-weeks into training camp in Nacogdoches, Tx., Hadl and I had about enough of our new offensive coordinator Ken Shipp’s meetings. We knew the offense better than he did. I’d called my own plays for going on seven years and worked my ass off in camp. We were at a bar after practice for a while, when Hadl and I started throwing back peppermint Schnapps. Mauck stood up when we were about four schnapps in, about 5:30, and said, “OK, time for the meeting.”

“We ain’t going,” I said.

Mauck argued with us for a while, but he knew Hadl and I weren’t going and we’d had our fill of Shipp. It was easy to get frustrated with Shipp. He was an Xs and Os guy who thought he knew everything there was to know about football because he watched tape back and forth, in slow-motion, forward and backwards until his eyes bled. Shipp was fine on the chalk board or scribbling on a piece of paper. The problem was Shipp didn’t really know shit when it came to actually playing the game full-speed. I always studied hard. I always watched film. I always enjoyed the chess game that was a part of football. But I learned the most on the field, when bullets were flying, because that’s how you learn to make adjustments and reads in a split second. Hadl had 14-years in the league. Shipp held a meeting just for the sake of holding a meeting, so Hadl and I decided to pass.

We didn’t know Bum was going to gather the entire team together and tell the team just how proud he was of the hard work we’d put in for three-weeks under steamy Texas conditions.

“I want to congratulate everybody,” Bum told the team. “It’s been long and hot and you all have done a great job. Everyone’s worked hard. Everyone’s been committed. No one’s been late to any practices or meetings..."

That’s when Mauck shouted at Bum.

“Oh, yeah? What about your quarterbacks?”

Bum looked around the room.

“Dan? John? … Pastorini? Hadl?”

John and I were in no shape to leave the bar. It was one of those nights. We both felt like cutting loose and we did. Around 11 p.m., we decided we should get back to our dorms and make amends with our teammates. I pulled into Jack In The Box to order about 50 hamburgers for the guys. As I tried to order the food, stumbling and stammering as I shouted at the Jack clown, Hadl got sick in my new truck. He literally was falling down drunk. I kicked open his door and he started puking on the ground, as I held him by the back of his shirt. He kept puking, until I pulled up my truck to the drive-thru window and he fell out the door into a thick blackberry bush that was about four-feet high, and a puddle of his own puke. I ran around the truck, pulled him out of the bush and dragged Hadl into the bed of my truck, because he smelled so bad. He had cuts on his arms and neck, scratches all over his face and was dripping with puke and beer. I picked up the bags of hamburgers, grabbed one and stuck it out the window in John’s face as I drove off back to camp, just to be a smartass.

“Want a cheeseburger, John?”

He groaned and rolled over in the bed of the truck. When we got back to the dorm, it only got worse. The vets were hazing the rookies with fire extinguishers, spraying powder everywhere. Hadl turned purple. At breakfast the next morning, Hadl and I had Schnapps hangovers, which are the worst, and we sat side-by-side, just completely raw. Bum sat down in front of us.

“What in the hell were you two doing?”

It was as if we rehearsed our reply, but we didn’t. Simultaneously, Hadl and I told Bum, “Coach, it seemed like the right thing to do at the time.”

Bum laughed and said, “You know I gotta fine you.”

“Yeah, put it on the tab,” I said.

The friction with Shipp got to be pretty deep-ceded. Before warm-ups every day we did these scrimmage plays called take-offs. The first-team offense, then the second-team offense, jogged through some simple plays. It was easy stuff, just to get the blood going and get warmed up.

When Hadl stepped up to the line after our long night out, Shipp called out a play neither of us knew and said, “OK, run it!”

“What is that?” John told him.

“Well, if you would have been at the meeting last night you’d know what it was.”

I was about to step in and tell Shipp what he could do with his damn meeting, but Hadl handled it. Here was John Hadl, 14-years in the league, one of the best quarterbacks in history, old No. 21. And this asshole was trying to treat him like a middle-schooler?

“Hey, mother fucker,” Hadl told Shipp, “just tell me the play and I’ll run it.”

Shipp mumbled something and then gave Hadl another play to run.

On top of the fine Bum gave us, John and I had to run a mile after practice and we spent it just laughing our asses off about the night before, imitating Shipp and laughing at his dumb ass.

It was just an ongoing thing between Shipp and me, just growing tension and frustration. He just had this power trip thing going, like he had to show me how much football he knew. We started the season hot, winning three of our first four games, but things began unraveling after that. We were just a team that needed to come together and needed a jolt of good luck. Except for Robert Brazile, most of our draft picks in ’75 and ’76 didn’t work out. We traded away a kid I thought would be pretty good – Steve Largent. And John Matuszak, who we took No. 1 overall in ’73, didn’t work out with us, went AWOL and wound up in the World Football League, before latching on with the Raiders. Bum was putting his stamp on the team with hard-working guys that maybe didn’t grab a lot of headlines or look pretty, but got the job done. He said, “I want players that work like country kids work. Get up early and just get the job done.”

I liked the way we had guys who were hungry and weren’t trying to impress anyone. We had guys that just wanted to play. We picked up late-round picks and free agents that just bought into what Bum was selling – Rob Carpenter, Mo Towns, Tim Wilson, Ken Kennard, George Reihner, Mike Reinfeldt. The epitome of them all was our kicker, Toni Fritsch. He was a frumpy, short, Austrian with a spare tire, a thick mustache and wore football pants that were two sizes too big. But man, could he kick.

Toni walked onto the practice field one day, Bum looked at him, shook his head and said, “Toni, you look like you’ve got a small Armenian family living in those pants.”

Toni made everybody laugh and took pride in making clutch kicks. I was his holder.

“I have ice-water in my veins,” Toni told me.

At Green Bay the second week of the season, the field-goal team rushed out late in the half to kick a field goal and Toni was nervous as hell, pulling on his pants, fidgeting, trying to rush to get lined up. As I took a knee and started counting players to make sure we were set, his eyes were the size of saucers and he told me in his accent, “Hurry, Dante, hurry, Dante.”

Right before I took the snap, I turned and looked at him.

“How’s that ice-water working out, Toni?”

We were close to turning the corner. We beat the Steelers in the ‘Dome to go 3-1, then things started unraveling. Shipp took it upon himself to figure out that my reads and checks were the problem.

During a midseason slump, Shipp was clicking and clicking the remote as we watched tape in a meeting room. He kept telling me what I should have been looking for from every guy on the opposing defense on every snap. It took him an hour and a half to run through 15 plays.

“You should have read the cornerback’s right foot,” he told me.

“You should have seen the defensive ends line up six-inches further outside,” he said.

It was just meaningless bullshit, on and on. Finally, I just reached over, grabbed the clicker out of his hand and threw it.

“Give me that damn thing,” I told him.

I started the video and rattled off everything I saw in real time, as the film was moving, without stopping the tape once.

I told Shipp, “Now tell me what they’re doing. Now tell me what the keys are. You can’t, can you?”

“You know what I see? I see the strong safety up, so I’m looking for a three-sky here. OK, now the safeties are deep, I’m looking for either a weak rotation or a double zone here.”

Sure enough, everything that I said would happen, happened on both plays. I ran through the whole damn film without stopping it once. I got most of the reads perfect. I called every check, perfect.

“I don’t need your goddamn, ‘Well, when his feet are like this, you need to look for that.’ Screw that, Ken. That’s not how it works. I don’t need to hear, ‘When he’s leaning this way, or looking over here, do this’ I don’t need that shit.”

I snapped my fingers.

“I have this much time to react and you’re wasting my time with this little meaningless bullshit.”

I walked out of the room. It was a bad year, not anything like what we expected. When we finished 8-6, I convinced myself that my divorce and the accidents hadn’t weighed on my mind. Usually, I’m always able to set things aside and focus on the games, but they probably were a distraction at some level.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"right","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12025}

I got beat up pretty good all year. I broke a couple of ribs, got my bell rung a few times and my collarbone and shoulder constantly were sore. That game we won against Pittsburgh was the most physical game any of us had ever played in. They were the team to beat and we got into an absolute war with them. I got carried off the field, Hadl got hurt and by the end of the game Guido Merkens, a utility guy and receiver, was taking snaps. The next day there were 23 players on the injured list between the two teams. I’d never seen a game when both teams were down to their third-string quarterbacks. Terry Bradshaw got hurt, Mike Kruczek got hurt and Tony Dungy was taking snaps for them. It was a bloodbath.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"right","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12025}

I got beat up pretty good all year. I broke a couple of ribs, got my bell rung a few times and my collarbone and shoulder constantly were sore. That game we won against Pittsburgh was the most physical game any of us had ever played in. They were the team to beat and we got into an absolute war with them. I got carried off the field, Hadl got hurt and by the end of the game Guido Merkens, a utility guy and receiver, was taking snaps. The next day there were 23 players on the injured list between the two teams. I’d never seen a game when both teams were down to their third-string quarterbacks. Terry Bradshaw got hurt, Mike Kruczek got hurt and Tony Dungy was taking snaps for them. It was a bloodbath.

They returned the favor in another physical game in Pittsburgh and we just kept sliding after that. We didn’t make the playoffs, but after ’77 the Steelers knew and we knew that we would be their toughest opponent from that point on. The one thing Bum established once and for all in ’77 was a roster of guys that wouldn’t back down from any fight, anywhere. We were as close-knit a team as I’d ever been a part of. Sure, the way we played was taking its toll on all of us, but everyone was hungry and everyone was hurt. We didn’t care what we had to do, we were going to be there for our teammates every Sunday unless we literally could not stand up.

I started relying heavily on pills to keep me going. I didn’t even know what they were, but they kept us on the roster and they kept us able to function off the field, too. I took mostly Desoxyn, Red-and-Yellows and Black Mollies. I took Desoxyn for hangovers. I took handfuls of Red-and-Yellows for pain, sometimes two or three times over the course of a game. I took Desoxyn to get energized. I started thinking I could control how I felt pretty easily. If I felt shitty, I took a pill to make myself feel better. If I felt real good, I took a pill to mess myself up. It’s like I was chemically controlled.

I mean, when I was a rookie one of my linemen, Bob Young, talked about taking steroids. I was sure a lot of guys were taking steroids by ’77, just like a lot of guys couldn’t function without pain pills. But nobody asked and nobody cared, least of all me. Those guys were protecting my ass, you think I’m going to care? You think anyone cared? None of it was under doctor’s supervision. Some guys were taking drugs to a level where no man should go. It’s how you survived.

On off days, we went just as hard. Sometimes we had Mondays off, sometimes we had Tuesdays. My biggest party night was Thursday. I could raise hell on Thursdays, then be done until after the game on Sunday. We’d hit Happy Hour, get a little buzz going and then start looking for girls. I always had the attitude of, I’m just going to be myself. I couldn’t be a phony, for better or worse. Bum didn’t care what you were or where you were from, so long as you played. If you did what you were told, showed up and played hard, he didn’t care. He didn’t care if you had long hair. He didn’t care if you were black or white. He just wanted you to do your job. Sometimes, Bum gave me a couple-hundred bucks and said, “Take the guys out and make sure everybody has a good time.”

It was a camaraderie thing and I was social chairman. We rented a place over by the Savannah Club near town and we had a room where we’d have barbecue, pizza and a bunch of beer. We’d drink for a couple of hours, hang out, then go our separate ways. We owned whatever club and disco we walked into, places like Daddy’s Money, Friday’s, Caligula’s, Sam’s Boat, Vic Taylor’s Namedropper Club, Gilley’s, whatever. The Oilers were becoming the biggest thing in town.

When I walked into a club, I always felt the eyes on me. It’s the same thing I felt when I first walked into the cafeteria at Santa Clara. I was the blue-chipper. I was the guy that was supposed to save the Oilers and I had yet to live up to that tag. Fans respected the way I played, but whenever we fell short like in ’77, it was open season on me.

By the time the season ended, all the papers and reporters picked apart my game. They said I was under-achieving. They wondered if I had what it took. Nothing hurt more than people calling me a loser or saying I should be traded. I had my car vandalized again after a game. I had played seven years in the NFL, but not once in a playoff game. I heard so many people blaming me, I started thinking maybe it was me. When I went home at the end of the season, I decided that if we didn’t make the playoffs in 1978, things might need to change.

Be looking for the book at bookstores near you!

Thanks,

John Lopez

He was involved in a tragic speed boating accident. He beat “Big Daddy” Don Garlits and all of drag racing’s best. He was the hero in the most triumphant return an NFL team ever received. He never backed down from anything or anyone, falling into notorious scrapes and life-altering lows. He married a Playboy model and posed for Playgirl. He dated Farrah Fawcett and was the most iconic figure in a Wild West era when Texas oil boomed and gluttony prevailed. Dan Pastorini never has told the whole story. Until now. This is the story of a gifted, hard-driving kid from California who never stopped going fast or chasing dreams.

No matter how much flak he took.

The following is an excerpt of the new book entitled "Taking Flak: My Life in the Fast Lane." It's co-authored by Pastorini and me and we would love if you guys would check out the excerpt and see if this book is something that would be of interest to you.

A few weeks before training camp in 1977, Don Meredith put together a quarterback legends charity golf tournament in Hawaii. It was a great event and a good time for me to get away. Some of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history were invited, as well as quarterbacks of my era like Roger Staubach and Tommy Kramer. Bobby Layne was there. Billy Kilmer. Johnny Unitas. Sonny Jurgenson. It was a posh event, sponsored by a hotel chain and supported by huge corporate sponsors. Bobby Layne was social chairman, so it basically was three days of golf, booze and stories.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"left","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12023}

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"left","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12023}

“Throw the ball up here,” Kilmer shouted. “Hit me, Dante. Can you hit me?”

Naturally, I wasn’t going to let a chance to show off pass me by. I cocked my arm and threw a perfect spiral as hard as I could. The ball sailed perfectly over their heads, above the balcony, above the next floor and hit a 10th-story balcony.

Jenkins turned to Bobby Layne and said, “Did you see that? Can you believe the arm strength in that kid? Can you believe he threw a football up 10-stories?”

Unitas chimed in, “Yeah, but his receiver was on the fifth floor.”

I laughed when I heard what Unitas said, but those were the kinds of comments that grated on me. That’s how my career was defined. He’s got a great arm, but …

Another quarterback legend, John Hadl, helped me a lot in 1977. He was a 14-year veteran that had seen it all. He convinced me to just keep working like I was working and keep playing hard. Hadl and I got along great, too, because he really knew football and liked having a good time off the field.

About three-weeks into training camp in Nacogdoches, Tx., Hadl and I had about enough of our new offensive coordinator Ken Shipp’s meetings. We knew the offense better than he did. I’d called my own plays for going on seven years and worked my ass off in camp. We were at a bar after practice for a while, when Hadl and I started throwing back peppermint Schnapps. Mauck stood up when we were about four schnapps in, about 5:30, and said, “OK, time for the meeting.”

“We ain’t going,” I said.

Mauck argued with us for a while, but he knew Hadl and I weren’t going and we’d had our fill of Shipp. It was easy to get frustrated with Shipp. He was an Xs and Os guy who thought he knew everything there was to know about football because he watched tape back and forth, in slow-motion, forward and backwards until his eyes bled. Shipp was fine on the chalk board or scribbling on a piece of paper. The problem was Shipp didn’t really know shit when it came to actually playing the game full-speed. I always studied hard. I always watched film. I always enjoyed the chess game that was a part of football. But I learned the most on the field, when bullets were flying, because that’s how you learn to make adjustments and reads in a split second. Hadl had 14-years in the league. Shipp held a meeting just for the sake of holding a meeting, so Hadl and I decided to pass.

We didn’t know Bum was going to gather the entire team together and tell the team just how proud he was of the hard work we’d put in for three-weeks under steamy Texas conditions.

“I want to congratulate everybody,” Bum told the team. “It’s been long and hot and you all have done a great job. Everyone’s worked hard. Everyone’s been committed. No one’s been late to any practices or meetings..."

That’s when Mauck shouted at Bum.

“Oh, yeah? What about your quarterbacks?”

Bum looked around the room.

“Dan? John? … Pastorini? Hadl?”

John and I were in no shape to leave the bar. It was one of those nights. We both felt like cutting loose and we did. Around 11 p.m., we decided we should get back to our dorms and make amends with our teammates. I pulled into Jack In The Box to order about 50 hamburgers for the guys. As I tried to order the food, stumbling and stammering as I shouted at the Jack clown, Hadl got sick in my new truck. He literally was falling down drunk. I kicked open his door and he started puking on the ground, as I held him by the back of his shirt. He kept puking, until I pulled up my truck to the drive-thru window and he fell out the door into a thick blackberry bush that was about four-feet high, and a puddle of his own puke. I ran around the truck, pulled him out of the bush and dragged Hadl into the bed of my truck, because he smelled so bad. He had cuts on his arms and neck, scratches all over his face and was dripping with puke and beer. I picked up the bags of hamburgers, grabbed one and stuck it out the window in John’s face as I drove off back to camp, just to be a smartass.

“Want a cheeseburger, John?”

He groaned and rolled over in the bed of the truck. When we got back to the dorm, it only got worse. The vets were hazing the rookies with fire extinguishers, spraying powder everywhere. Hadl turned purple. At breakfast the next morning, Hadl and I had Schnapps hangovers, which are the worst, and we sat side-by-side, just completely raw. Bum sat down in front of us.

“What in the hell were you two doing?”

It was as if we rehearsed our reply, but we didn’t. Simultaneously, Hadl and I told Bum, “Coach, it seemed like the right thing to do at the time.”

Bum laughed and said, “You know I gotta fine you.”

“Yeah, put it on the tab,” I said.

The friction with Shipp got to be pretty deep-ceded. Before warm-ups every day we did these scrimmage plays called take-offs. The first-team offense, then the second-team offense, jogged through some simple plays. It was easy stuff, just to get the blood going and get warmed up.

When Hadl stepped up to the line after our long night out, Shipp called out a play neither of us knew and said, “OK, run it!”

“What is that?” John told him.

“Well, if you would have been at the meeting last night you’d know what it was.”

I was about to step in and tell Shipp what he could do with his damn meeting, but Hadl handled it. Here was John Hadl, 14-years in the league, one of the best quarterbacks in history, old No. 21. And this asshole was trying to treat him like a middle-schooler?

“Hey, mother fucker,” Hadl told Shipp, “just tell me the play and I’ll run it.”

Shipp mumbled something and then gave Hadl another play to run.

On top of the fine Bum gave us, John and I had to run a mile after practice and we spent it just laughing our asses off about the night before, imitating Shipp and laughing at his dumb ass.

It was just an ongoing thing between Shipp and me, just growing tension and frustration. He just had this power trip thing going, like he had to show me how much football he knew. We started the season hot, winning three of our first four games, but things began unraveling after that. We were just a team that needed to come together and needed a jolt of good luck. Except for Robert Brazile, most of our draft picks in ’75 and ’76 didn’t work out. We traded away a kid I thought would be pretty good – Steve Largent. And John Matuszak, who we took No. 1 overall in ’73, didn’t work out with us, went AWOL and wound up in the World Football League, before latching on with the Raiders. Bum was putting his stamp on the team with hard-working guys that maybe didn’t grab a lot of headlines or look pretty, but got the job done. He said, “I want players that work like country kids work. Get up early and just get the job done.”

I liked the way we had guys who were hungry and weren’t trying to impress anyone. We had guys that just wanted to play. We picked up late-round picks and free agents that just bought into what Bum was selling – Rob Carpenter, Mo Towns, Tim Wilson, Ken Kennard, George Reihner, Mike Reinfeldt. The epitome of them all was our kicker, Toni Fritsch. He was a frumpy, short, Austrian with a spare tire, a thick mustache and wore football pants that were two sizes too big. But man, could he kick.

Toni walked onto the practice field one day, Bum looked at him, shook his head and said, “Toni, you look like you’ve got a small Armenian family living in those pants.”

Toni made everybody laugh and took pride in making clutch kicks. I was his holder.

“I have ice-water in my veins,” Toni told me.

At Green Bay the second week of the season, the field-goal team rushed out late in the half to kick a field goal and Toni was nervous as hell, pulling on his pants, fidgeting, trying to rush to get lined up. As I took a knee and started counting players to make sure we were set, his eyes were the size of saucers and he told me in his accent, “Hurry, Dante, hurry, Dante.”

Right before I took the snap, I turned and looked at him.

“How’s that ice-water working out, Toni?”

We were close to turning the corner. We beat the Steelers in the ‘Dome to go 3-1, then things started unraveling. Shipp took it upon himself to figure out that my reads and checks were the problem.

During a midseason slump, Shipp was clicking and clicking the remote as we watched tape in a meeting room. He kept telling me what I should have been looking for from every guy on the opposing defense on every snap. It took him an hour and a half to run through 15 plays.

“You should have read the cornerback’s right foot,” he told me.

“You should have seen the defensive ends line up six-inches further outside,” he said.

It was just meaningless bullshit, on and on. Finally, I just reached over, grabbed the clicker out of his hand and threw it.

“Give me that damn thing,” I told him.

I started the video and rattled off everything I saw in real time, as the film was moving, without stopping the tape once.

I told Shipp, “Now tell me what they’re doing. Now tell me what the keys are. You can’t, can you?”

“You know what I see? I see the strong safety up, so I’m looking for a three-sky here. OK, now the safeties are deep, I’m looking for either a weak rotation or a double zone here.”

Sure enough, everything that I said would happen, happened on both plays. I ran through the whole damn film without stopping it once. I got most of the reads perfect. I called every check, perfect.

“I don’t need your goddamn, ‘Well, when his feet are like this, you need to look for that.’ Screw that, Ken. That’s not how it works. I don’t need to hear, ‘When he’s leaning this way, or looking over here, do this’ I don’t need that shit.”

I snapped my fingers.

“I have this much time to react and you’re wasting my time with this little meaningless bullshit.”

I walked out of the room. It was a bad year, not anything like what we expected. When we finished 8-6, I convinced myself that my divorce and the accidents hadn’t weighed on my mind. Usually, I’m always able to set things aside and focus on the games, but they probably were a distraction at some level.

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"right","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12025}

TexAgs

{"Module":"photo","Alignment":"right","Size":"large","Caption":"","MediaItemID":12025}

They returned the favor in another physical game in Pittsburgh and we just kept sliding after that. We didn’t make the playoffs, but after ’77 the Steelers knew and we knew that we would be their toughest opponent from that point on. The one thing Bum established once and for all in ’77 was a roster of guys that wouldn’t back down from any fight, anywhere. We were as close-knit a team as I’d ever been a part of. Sure, the way we played was taking its toll on all of us, but everyone was hungry and everyone was hurt. We didn’t care what we had to do, we were going to be there for our teammates every Sunday unless we literally could not stand up.

I started relying heavily on pills to keep me going. I didn’t even know what they were, but they kept us on the roster and they kept us able to function off the field, too. I took mostly Desoxyn, Red-and-Yellows and Black Mollies. I took Desoxyn for hangovers. I took handfuls of Red-and-Yellows for pain, sometimes two or three times over the course of a game. I took Desoxyn to get energized. I started thinking I could control how I felt pretty easily. If I felt shitty, I took a pill to make myself feel better. If I felt real good, I took a pill to mess myself up. It’s like I was chemically controlled.

I mean, when I was a rookie one of my linemen, Bob Young, talked about taking steroids. I was sure a lot of guys were taking steroids by ’77, just like a lot of guys couldn’t function without pain pills. But nobody asked and nobody cared, least of all me. Those guys were protecting my ass, you think I’m going to care? You think anyone cared? None of it was under doctor’s supervision. Some guys were taking drugs to a level where no man should go. It’s how you survived.

On off days, we went just as hard. Sometimes we had Mondays off, sometimes we had Tuesdays. My biggest party night was Thursday. I could raise hell on Thursdays, then be done until after the game on Sunday. We’d hit Happy Hour, get a little buzz going and then start looking for girls. I always had the attitude of, I’m just going to be myself. I couldn’t be a phony, for better or worse. Bum didn’t care what you were or where you were from, so long as you played. If you did what you were told, showed up and played hard, he didn’t care. He didn’t care if you had long hair. He didn’t care if you were black or white. He just wanted you to do your job. Sometimes, Bum gave me a couple-hundred bucks and said, “Take the guys out and make sure everybody has a good time.”

It was a camaraderie thing and I was social chairman. We rented a place over by the Savannah Club near town and we had a room where we’d have barbecue, pizza and a bunch of beer. We’d drink for a couple of hours, hang out, then go our separate ways. We owned whatever club and disco we walked into, places like Daddy’s Money, Friday’s, Caligula’s, Sam’s Boat, Vic Taylor’s Namedropper Club, Gilley’s, whatever. The Oilers were becoming the biggest thing in town.

When I walked into a club, I always felt the eyes on me. It’s the same thing I felt when I first walked into the cafeteria at Santa Clara. I was the blue-chipper. I was the guy that was supposed to save the Oilers and I had yet to live up to that tag. Fans respected the way I played, but whenever we fell short like in ’77, it was open season on me.

By the time the season ended, all the papers and reporters picked apart my game. They said I was under-achieving. They wondered if I had what it took. Nothing hurt more than people calling me a loser or saying I should be traded. I had my car vandalized again after a game. I had played seven years in the NFL, but not once in a playoff game. I heard so many people blaming me, I started thinking maybe it was me. When I went home at the end of the season, I decided that if we didn’t make the playoffs in 1978, things might need to change.

Be looking for the book at bookstores near you!

Thanks,

John Lopez

Never miss the latest news from TexAgs!

Join our free email list